netflix documentary details abercrombie & fitch controversies

Picture this: It’s 2005 and you just got dropped off at the mall with your friends. No other thought exists in your mind but to make a beeline for the hottest store in the mall. A whiff of cologne enters your nose first, and then your ears are greeted by the booming sound of techno music. Three beautiful teenagers stand at the register looking like they are bored out of their minds. Racks of polos and jeans fill the room and you look around in awe, not knowing where to go first. In the midst of it all, the walls are adorned with half-naked photos of ripped male models and golden retrievers, all under a sign that reads none other than Abercombie and Fitch.

Abercrombie and Fitch was the place to shop at the height of its popularity. Mall culture was at its highest and the mall was the “cool” spot to hang out with friends. Before social media told everyone which trends were popular, teenagers would run to the mall to see the newest styles. A&F was advertised everywhere and seen on everyone. Celebrities such as Ashton Kutcher, Taylor Swift, Channing Tatum, Jennifer Lawrence and Heidi Klum were all spotted decked out in A&F’s hottest styles. From the low-rise jeans to the shirts embroidered with the signature Abercrombie logo, there was no shortage of “coolness” in this store.

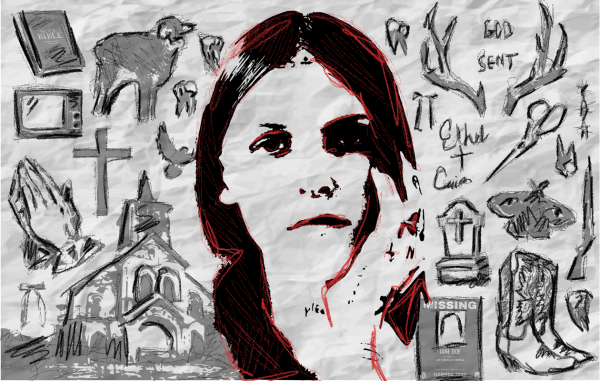

Abercrombie sold exclusivity. Consumers wanted belonging. Abercrombie created belonging through exclusion. These two concepts are opposites, but they worked together to create a culture that was elitist. People bought into this, which only fortified the culture even more. Behind all of the glitz and glamor, however, lies some ugly truths. Abercrombie created a culture that not only thrived off exclusion but its ideals were majorly rooted in multiple forms of discrimination. As seen in Netflix’s original documentary, “White Hot: The Rise and Fall of Abercrombie and Fitch,” this store proved to be very problematic.

Abercrombie had been around for about a hundred years before it was transformed into the store we all so vividly remember. Michael Jeffries took over the company from Les Wexner, becoming CEO in 1992, and he changed the course of the company dramatically. Abercrombie capitalized off of this exclusive culture, mostly because at this time, American culture was not inclusive to individuals who did not fit the perceived beauty standard. Although these issues remain in a sense today, the prevalence of this toxic culture was at an all-time high in the late ‘90s and early 2000s. What has changed, however, is people’s tendency to condemn these behaviors and speak out against them.

Abercrombie’s aesthetic was “All-American,” imitating the infamous ultra-masculine and popular boys. The iconic black and white photos of buff male models, so famously produced by Bruce Weber, created a brand image that made it so recognizable. Even the bags had washboard abs printed on them.

Abercrombie marketed exclusion and used that to its benefit, ultimately creating a culture that left most feeling excluded and under-represented. Abercrombie’s brand image created a middle ground between sex appeal and preppy American culture and this was heightened through their marketing techniques. Abercrombie’s target audience was teenagers, those who crave desirability and belonging in their most impressionable years. The toxic culture created by Abercrombie ruined so many teenagers’ fragile self-images with unachievable beauty standards and a lack of diversity.

One of the most concerning aspects of “White Hot” was how much of an emphasis Abercrombie put into its hiring practices. To work as a “Brand Rep” at Abercrombie, one had to be “attractive” enough and pass company standards. There was a literal handbook of what managers should look for when hiring employees. For instance, dreadlocks were deemed unacceptable in male brand reps, but “clean” hairstyles were approved. This discriminatory nature of hiring was unethical, but it somehow persisted for many years without question. Brand Reps would then get hours based on how attractive they were perceived to be. If they worked at the front of the store, that is how they would know that they were pretty enough to be working. However, if Brand Reps were sent to work in the back, they were deemed as “ugly” and unfit to be working up front.

An example of Abercrombie’s horrendous hiring practices was when a teenager named Samantha Elauf applied for a job at Abercrombie and was rejected because she was wearing a hijab. She was told that her hijab did not comply with the company’s look policies. Elauf filed a complaint against Abercrombie with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and the brand refused to settle. Abercrombie appealed the case, comparing wearing a hijab to wearing a baseball cap. The case ended up going all the way to the Supreme Court, where Abercrombie argued that hiring Elauf would hurt their sales. In an 8-to-1 decision in favor of Elauf, the Supreme Court ruled that this case violates the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Racial discrimination claims were nothing new to Abercrombie, as this white-dominated brand rooted itself in discrimination during this time.

Eventually, enough was enough, and Abercrombie was brought to court by nine former employees. They sued for racial discrimination and wrongful hiring practices. Abercrombie then paid a $50 million settlement, under the condition that they would make some changes to their company. These “changes” took place in a consent decree, which was a set of regulations that Abercrombie was ordered to follow. These ordered changes were to enforce fair hiring, recruiting and marketing practices. However, there were no punishments if Abercrombie did not meet these expectations, and the consent decree did not force leadership to change.

In addition to these regulations, the court ordered Abercrombie to elect a diversity officer. Todd Corley became the first diversity officer for Abercrombie and initiated changes to push towards a more inclusive brand. Although the changes were semi-successful, there was still more work that needed to be done to achieve total diversity and inclusion within the brand.

Problems remained with the brand after this lawsuit, as Jeffries still played into the exclusionary culture he ultimately created. In an interview with a reporter in 2006, Jeffries said, “Are we exclusionary? Absolutely.” Jeffries elaborated further by saying, “Candidly, we go after the cool kids. We go after the attractive all-American kid with a great attitude and a lot of friends. A lot of people don’t belong, and they can’t belong.”

Seven years later, Benjamin O’Keefe decided to speak up about Jeffries’s remarks. At only 18 years old, he put together a petition for Jeffries to apologize for the offensive statements he had previously made. This petition sparked public controversy and people started to notice the issues within the company, which was finally a step in the right direction. O’Keefe mentioned that he went to meet the upper management so they could apologize for the statements made, but Jeffries was not present at the meeting. He relayed that he spoke to Corley, who at the time was the diversity officer, and he tried to convince him that the brand had made significant efforts to be more inclusive. O’Keefe responded by dropping copies of the signed petition in front of each executive in the meeting to prove his point that there were thousands of people who felt excluded by the brand.

All stars must burn out eventually, and like a star in its last stage of life, Abercrombie fizzled out just as fast as it gained popularity. The name of the documentary comes full circle, as Washington Post Senior Critic, Robin Givhan, discusses a brand’s lifecycle: “White hot brands always burn out.” After the court case, people started to realize the extent of the racist, discriminatory and exclusive ideals of this brand and decided to bring their business elsewhere. Abercrombie suffered in sales and Jeffries left the company in 2014.

Current CEO Fran Horowitz stepped in and gave Abercrombie a total brand makeover. Business strategies and marketing campaigns shifted towards inclusivity efforts. As a society, our culture is not the same as it was ten years ago, and those changes have made for a more inclusive mindset. Beauty standards have shifted and the perception of beauty is much broader. We used to live in a culture that was happy to exclude people. It was “cool” to exclude people. Abercrombie both followed this idea and contributed to it. Is our culture today completely accepting? No, it is not. There is still much room for growth when it comes to inclusivity, but we are taking a step in the right direction.

Today, Abercrombie is much different than it was back then. The clothes are stripped of aggressive logos to now reveal a much sleeker line of clothing. The quality of the pieces is extraordinary, with nicer fabrics and an overall polished look. The size options are much broader now, and Abercombie even has a line of jeans called “Curved Love” that is growing increasingly popular on social media. Jeans range in size from 23 to 37 with long and short varieties to cater to many customers.

Abercrombie has a whole section on its website dedicated to gender-inclusive clothing, which is something that juxtaposes Jeffries’ previous ideals for the brand. Jeffries campaigned for highly feminine and highly masculine versions of clothing, and now Abercrombie markets itself as accepting of all genders. With Abercrombie’s new marketing tactics, everyone is represented and everyone can be the “cool kid.” Abercrombie models today represent different sizes and races, which is something that many never thought would occur.

Although there is much left to be done to achieve total inclusivity in the fashion industry, brands are in a better place now than they were in past decades. Abercrombie was exposed to its core through this documentary, but it exemplifies how much our society has grown: People are now more apt to speak out against exclusion and advocate for inclusion.

Support Student Media

Hi! I’m Catie Pusateri, A Magazine’s editor-in-chief. My staff and I are committed to bringing you the most important and entertaining news from the realms of fashion, beauty and culture. We are full-time students and hard-working journalists. While we get support from the student media fee and earned revenue such as advertising, both of those continue to decline. Your generous gift of any amount will help enhance our student experience as we grow into working professionals. Please go here to donate to A Magazine.