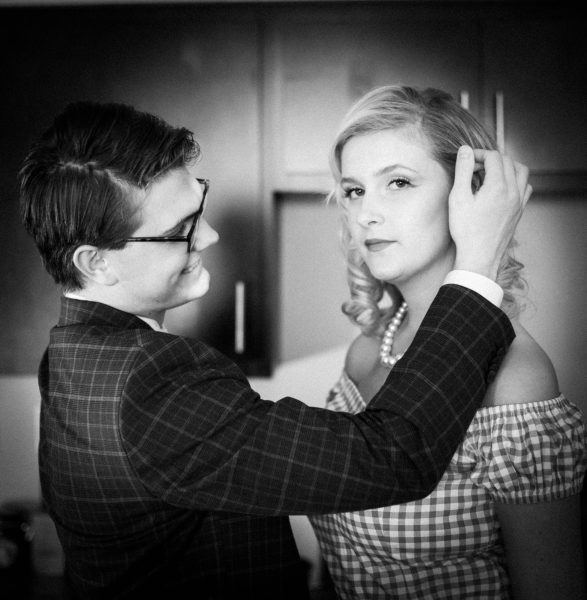

Models: Ashton Kish and Julia Reading

Stylists: Emma Foos and Steph Mossop

Imagine being told your purpose in life is your husband. You wear the apron, cook the meals, raise the children—if you dare dream of more, you’re selfish.

In the 1950s, women were expected to conform to a specific image of femininity. Their primary roles were as wives and mothers, with society dictating that fulfillment should come from serving their husbands and raising their children. With their ambitions trapped behind the bars of domesticity, their place was the home. Women who sought careers, or even an independent life outside of marriage, were seen as rebelling against their “natural” roles.

Higher education and full-time work were the exception, not the rule. Although college slowly became more commonplace for women, it was encouraged for one purpose: preparing to be the ideal wife and mother. Women were not expected to leave college with career aspirations. Instead, their goal was to earn the so-called “M.R.S. Degree”—finding a husband. The Ivy Leagues were still off-limits as male-only spaces and women were taught to study “feminine” subjects like education and nursing.

Commercials, television shows and advertisements were rife in their depictions of women as the “perfect wife.” They were seen with ear-to-ear smiles while serving dinner or scrubbing the dishes. Some advertisements even included blatant digs at women’s intelligence and capabilities, such as a ketchup ad with the caption “You mean a woman can open it?” or an even more daring Van Huesen ad imploring husbands to “show her it’s a man’s world” as the wife serves breakfast on her knees. These messages weren’t just selling products; they were selling an ideal by quietly reinforcing a narrative of female subservience that made it easier to confine women to the home.

All the while, reproductive choices were largely controlled by male lawmakers and medical professionals. Birth control was not yet widely available, and many women had limited access to safe contraceptives. Abortion was illegal in most places, forcing many into dangerous, life-threatening situations. Consent, even in marriage, was not a recognized concept. The choice of if and when women wanted to be mothers was out of their hands.

While the 1950s had women in the confines of domestic life, the following decades were a transformative period for women’s rights. During this time, the second-wave feminist movement ignited social, political and legal change, empowering women to claim control over their bodies, careers and futures.

“When she stopped conforming to the conventional picture of femininity, she finally began to enjoy being a woman,” said second-wave feminist writer Betty Friedan in “The Feminine Mystique.” Her words echoed the empowering sense of freedom many women experienced as they tore through the bars of domestic confinement, reclaiming their lives as their own.

The fight for gender equality gained traction, challenging the traditional roles women had been boxed into. This movement emphasized issues like workplace discrimination, reproductive rights and sexual freedom, all of which had either been neglected or outright denied in previous decades.

The Food and Drug Administration gave the official clearance of birth control in 1960, marking a key milestone in women reclaiming their autonomy. The birth control pill became a symbol of freedom, giving women more control over their choice to have a family. This newfound freedom allowed them to pursue education or careers without fear of pregnancy.

Roe v. Wade in 1973 cemented reproductive rights as a constitutional issue. This monumental Supreme Court decision was not just about the right to terminate a pregnancy, it was about having a choice, something historically denied to women.

Women were also making strides in the workplace. The Equal Pay Act of 1963 and The Civil Rights Act of 1964 protected women against unfair labor practices. While the wage gap was still present, women could finally represent themselves in professional settings.

We exited this era of progression feeling optimistic about what women could achieve. For decades, we’ve enjoyed the freedoms that generations of women fought for without realizing the fragility of those rights. It wasn’t until recently we were abruptly reminded that these rights were never inherent.

Just two years ago, women’s reproductive rights faced major setbacks in the United States. Roe v. Wade was overturned, allowing states to employ their own abortion restrictions, leading to near-total or total abortion bans. At the same time, restrictions have increased to access contraceptives like Plan B.

In addition to legal implications, there has been a shift in the mindset of a “woman’s place” in society.

With legislation in many states attempting to strip away the freedoms hard-won in the 1970s, “traditional” lifestyles promoted on social media indicate a concerning regression.

A surprising number of women are willingly embracing the ‘Tradwife’ lifestyle with a troubling nostalgia for this ‘perfect wife’ creeping back into view. The Tradwife sensation on social media has stirred controversy on how modern women define their worth.

Prominent influencers like Hannah Neeleman (@ballerinafarm) and Gwen (@gwenthemilkmaid) are now broadcasting a lifestyle where women celebrate being subservient to their husbands and devoted entirely to home life. Tradwives embody a life of domestication, romanticizing homemaking, baking and caretaking. This phenomenon promotes traditional gender roles in a household, a narrative that feels awfully familiar. It has introduced a complicated dichotomy between traditional and feminist values and whether there can be a place for both in modern society.

While some argue women should be supported in their decision to embrace traditional gender roles if they choose, there’s concern this narrative may be part of a larger, propagandized agenda, similar to the media we saw in the ‘50s. By idealizing a return to rigid domestic roles, the trend could subtly encourage a lifestyle that makes women less likely to resist broader threats to their rights. The romanticization of this lifestyle may ultimately weaken collective efforts for gender equality and obscure the ongoing fight for women’s autonomy.

What was once a battle we thought we had won now calls us back to the front lines. Rights we took for granted are under threat again, and the fight for equality is far from over.

Support Student Media

Hi! I’m Kayla Friedman, A Magazine’s editor-in-chief. My staff and I are committed to bringing you the most important and entertaining news from the realms of fashion, beauty and culture. We are full-time students and hard-working journalists. While we get support from the student media fee and earned revenue such as advertising, both of those continue to decline. Your generous gift of any amount will help enhance our student experience as we grow into working professionals. Please go here to donate to A Magazine.