As of 2024, almost 90% of consumers say they have either purchased from or donated to a thrift store at some point— a 17% increase since 2022. Between 16% and 18% of consumers regularly shop at thrift stores per year. There’s no denying the rise of secondhand shopping, but how has it evolved over the years from being a charitable concept to a popular trend? How might this growth negatively impact low-income communities?

Second-hand shopping is not a new concept. Dating back to the 17th century, antique and “curiosity” shops were used to sell pre-owned goods to the common consumer. It wasn’t until the late 1800s, though, that certain shops began to sell used articles of clothing, as well.

Prior to this, even during this transitional period for second-hand stores, clothes were typically handmade and expensive; people would often wear them until they were worn to shreds and then would buy anew. In fact, most of the iconic thrift stores we know today began as charity shops organized by churches or local governments and seldom sold clothing.

The Salvation Army, for example, was founded in London in 1867 and originally provided church services, healthcare, and housing to underserved communities. It wasn’t until some of the biggest turning points of the 20th century, like the Great Depression and World Wars I and II, that thrift stores truly became synonymous with clothing, as the need for clothing and fabric for low-income families became more dire.

When did thrift stores become mainstream? The first major reported influx of thrift shopping was in the 1960s. During the hippie movement, the younger generations flocked to thrift stores to achieve the desired bohemian look. Since then, thrifting has gone through phases of popularity, but it traditionally retained its reputation as a resource to those in need. This was especially true once clothing became sold at department stores and became primarily off-the-rack and mass-produced.

During this new department store era, the 80s, 90s, and early 2000s, it was desirable to have the newest and best clothing. At this point, fashion had truly started to become the unsustainable industry it is today. Consumers would buy trendy outfits and frequently donate“old” ones as they went out of style. This phenomenon combined with thrifting’s preexisting history of being owned by churches and charity organizations cemented its reputation as something primarily for economically disadvantaged people.

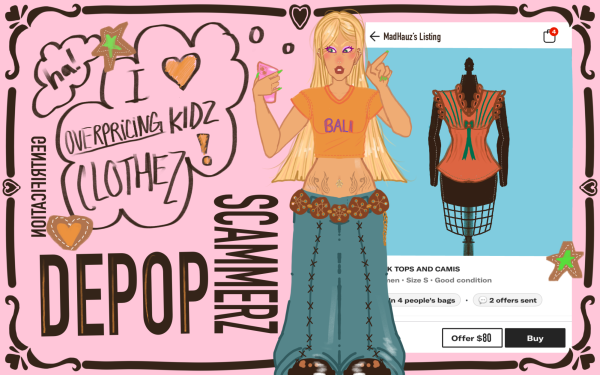

When assessing the thrifting climate of the present, most people would probably agree that it’s more popular than ever, and it is. Over 40% of Gen Z shops second-hand. This could be for a few reasons such as a new and rising push for sustainability, an emerging emphasis on originality through clothing, and the rise of resale platforms like Depop and Facebook marketplace. TikTok has also been a huge catalyst for the thrifting movement.

At face value, this all may seem great. This generation’s infatuation with thrifting may have a positive impact on reducing fast fashion and has already largely eradicated any stigma that may have been associated with the act of thrifting.

What are the negative implications? For one, the rising costs. The sheer demand for second-hand clothing is unlike it’s ever been before. Despite typically starting out as charity organizations, many major thrift chains have raised their prices significantly in response to the growing consumer interest. However, this seems unnecessary given that a 40% increase in the thrifting industry from 2021 resulted in 1.4 billion second-hand items being purchased in 2022.

As for consumers, modern thrifters frequently resell items online for well beyond their original thrift store price. To appeal to resale consumers, Depop users and other resellers typically take the highest quality and most trending items from the stores. Unfortunately, through this rise in popularity, low-income shoppers have had to take the brunt of the rising costs and the picked-over stores. Though there is still currently minimal research on the impacts, this conveys an attitude that people who are financially struggling don’t deserve quality and affordable clothes.

In an economic climate already strained by inflation, a looming recession, and widening wealth gaps, the gentrification of thrifting raises serious ethical concerns. As secondhand shopping shifts from a necessity to a trend, those who need it most are being left with dwindling options.

Support Student Media

Hi! I’m Kayla Friedman, A Magazine’s editor-in-chief. My staff and I are committed to bringing you the most important and entertaining news from the realms of fashion, beauty and culture. We are full-time students and hard-working journalists. While we get support from the student media fee and earned revenue such as advertising, both of those continue to decline. Your generous gift of any amount will help enhance our student experience as we grow into working professionals. Please go here to donate to A Magazine.