Artificial Intelligence (AI) has been around since the early 2010s. Apple’s “Siri” and Amazon’s “Alexa” are the most popular and digestible examples of how AI has been integrated into society. Various TikTok filters incorporate AI to generate an image based on a photo or the user’s live camera. According to Kaitlin Rogers, writer for .ART, this process is referred to as “generative art” in which a set of artistic parameters, such as a color palette or a theme to follow, are given to the AI, and it then creates art pieces based on the instructions given. Conversely, the same can be applied to writing. A quick Google search for an AI tool that writes essays, provides multiple websites that promote unique, fast and accurate essays. But is faster always better?

Some fields argue yes; the faster the better. AI has contributed to the progression of the medical field through its accuracy and reliability–removing the possibility of human error. According to the National Library of Medicine, specifically the Natural Center for Biotechnology Information, AI has several advantages in the industry, including the ability to grade diabetic retinopathy, accurately diagnose patients in a short amount of time and detect diabetic retinopathy in early stages by studying “mages at the granular level–something impossible for a human ophthalmologist to do.” Additionally, AI is being integrated into healthcare to better assist patients and doctors alike. For example, AI can quickly list on-call physicians and schedule appointments, answer questions related to prescription cost or alternatives and search available clinical tools and drugs to “[improve the overall] workflow in the hospital.”

Along with aiding scientific fields, AI can also assist in the art world. For physical artworks, especially those dating back decades and centuries, AI plays a major role in keeping them readily available for the public to view. Rogers believes that AI “can be used to monitor and maintain artworks” by searching for “detecting signs of deterioration or damage” to help “preserve artwork for future generations.” Additionally, much like a visual merchandiser, AI can generate potential ideas for museum layouts that best engage the audience and provide a more personalized experience with the art.

While AI pushes the boundaries of modern-day technology, is there a line to be drawn in the art world? Unlike scientific and mathematical-based industries that rely on accurate data and straightforward truths, art is subjective and there is no right or wrong. Does AI help or hinder the creative process, and is it a suitable replacement for human intelligence?

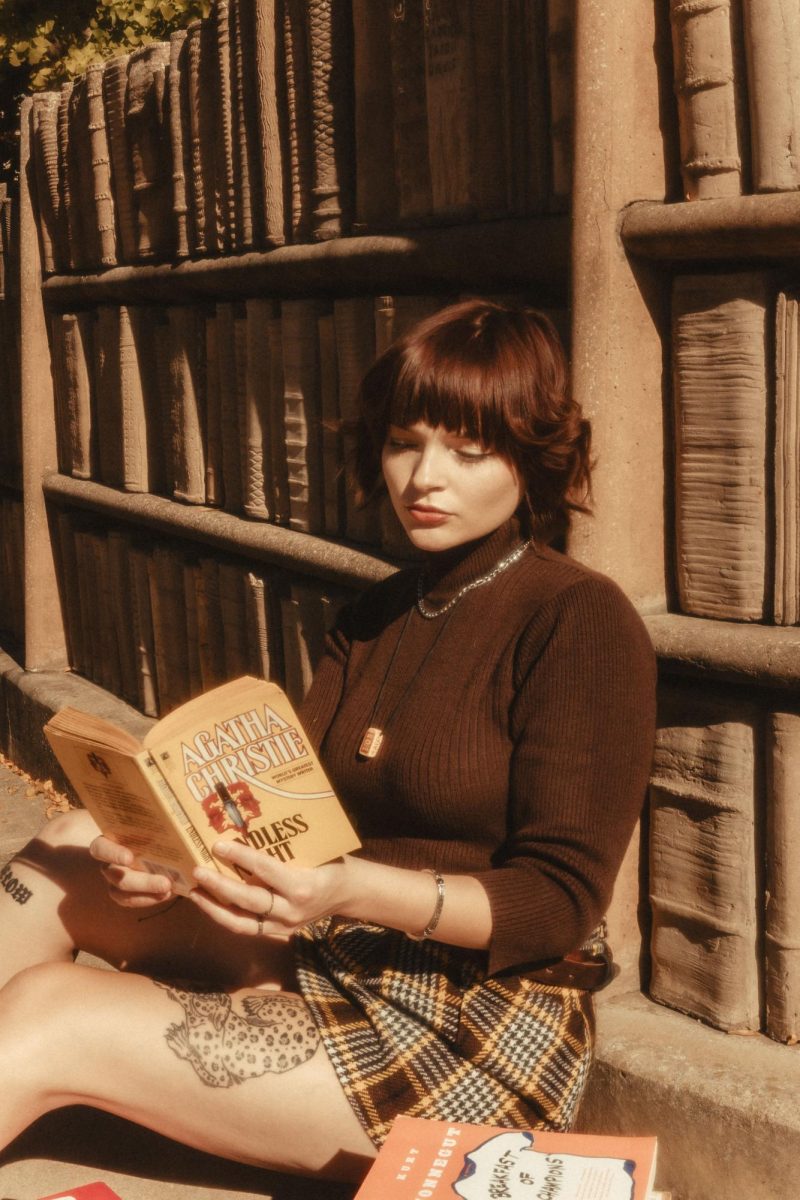

Catherine Wing, an English professor at Kent State University, shared her thoughts on the matter. Wing attended Brown University for her undergraduate degree and then received a Master of Fine Arts from the University of Washington. She teaches poetry at Kent State University and is a published author of two collections of poetry.

To her, Artificial Intelligence is a system “trained to look for and decipher patterns” that “can be quite experimental and exciting.” In her personal life, Wing uses Amazon’s “Alexa” at home; professionally, she uses Microsoft’s Outlook and its predictive feature to write emails. Her experience with AI is congruent with the majority of society, as AI has slowly been integrated into everyday life. In relation to writing, Wing believes AI can be thought of “as a tool.” She says, “A tool like a hammer or saw requires agency in that somebody is holding onto it, so it cuts the branch instead of the arm off.” In simpler terms, AI can be used to enhance ideas. For example, the popular web extension “Grammarly” provides structural, grammatical and spelling correction tools that do not generate work for you but edit pre-existing excerpts. When AI is thought of as a tool, “it can be an interesting device” and can be incorporated into the writing process as “step one in a ten-step process.”

On the other hand, AI has the potential to hinder the creative process. “If we let it stand in for us, we give it agency,” Wing claims. Poetry, specifically, is “an engagement of language as a means of communication.” It is designed to make you think and share some emotional connection. A common critique of AI is its lack of emotion in its writing. Wing explained that “if you ask AI to write you a poem, there’s no personal connection to the language or emotion.” To Wing, “poetry is about slowing down and paying attention,” whereas “AI is about doing things faster with little to no attention.” At its core, AI contradicts poetry in its need for speed. “Writing is really hard, and it’s hard for everybody,” Wing explains. AI can sometimes “lull the writer into a place of complacency” and is an “easy way out when you’re not thinking about what you’re writing anymore.” Moreover, “the danger is if you farm out your papers to AI, then you are not really forcing yourself to do the mental labor and think through an issue.” When someone is too reliant on AI, they may lose the ability to think for themselves and determine their opinion on certain topics. In the end “they no longer have the facility or training to think [these topics] through.”

Wing then brought up the “Turing Test.” According to Benjamin St. George and Alex Gillis of TechTarget, the Turning Test is named after its founder, Alan Turing, who was an English computer scientist, cryptanalyst, mathematician and theoretical biologist. Alan Turing theorized that a computer is artificially intelligent “if it can mimic human responses under specific conditions.” Three separate terminals are used, with a human in charge of two and a computer operating the other. One human poses as the questioner, whereas the other human and the computer both pose as respondents. Numerous questions are asked “within a specific subject area, using a specific format and context.” Afterward, the questioner must decide which response was the human’s and which one was the computer’s. St. George explained that “the test is repeated many times” and that if the questioner correctly identifies the responses in half of the test runs or less, “the computer is considered to have artificial intelligence” since the questioner “regards it as ‘just as human’ as the human respondent.” Wing states that “if we can’t do better more than 50% of the time, we are screwed because we ourselves cannot figure out a human over a machine.” She makes a great point; it seems dangerous to have computers that can mimic a human and convince the public of its humanity.

Sometimes, AI hurts more than it helps. It makes us question what our future is going to look like and if all creativity is going to be replaced with computer-based intelligence. Maybe art will become less meaningful as it loses human touch or literature will be less thought-provoking without the questions posed by the human brain. AI has proven its worth in fields that are not based on creativity or emotion. Yet, AI’s role in the arts has not been maximized in a way that allows artists to continue to be authentic. After all, Leonardo da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa” would not be as impressive if it was generated with a TikTok filter. Its essence lies in the painterly choices of the artist that seem impossible to the average viewer. While AI has both positive and negative consequences, there is still much to be investigated as technology advances.

Support Student Media

Hi! I’m Annie Gleydura, A Magazine’s editor-in-chief. My staff and I are committed to bringing you the most important and entertaining news from the realms of fashion, beauty and culture. We are full-time students and hard-working journalists. While we get support from the student media fee and earned revenue such as advertising, both of those continue to decline. Your generous gift of any amount will help enhance our student experience as we grow into working professionals. Please go here to donate to A Magazine.