kent state museum curator dr. sara hume on egyptian influence on 1920s fashion

When I was a child, my mom gave me a sticker book of 1920s fashion. At this point, I already loved historical fashion, and though the 1920s was not at the top of my list of favorite fashion decades, I still delved into it. One page that stood out was about the inspiration of Egyptian art and culture influencing the decade. Fast forward through a King Tut exhibit and an Egyptian mythology phase inspired by Rick Riordan’s “The Kane Chronicles,” 1920s fashion is still not my favorite, but each time I see the decade I can’t help but think about that sticker book with its page about Egyptian inspiration.

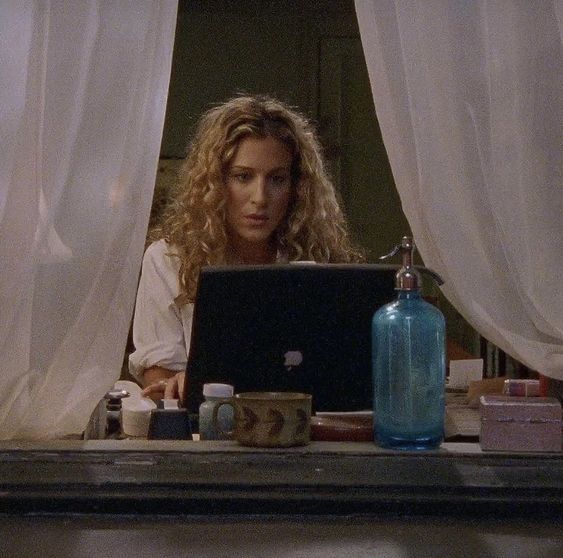

I interviewed Dr. Sara Hume, the Kent State University Museum curator, about Egyptomania in the 1920s. During our conversation, she showed me various 1920s garments influenced from Egyptian culture, including a hat inspired by Egyptian wigs and a beautiful 1917 cape with elaborate embroidery featuring hieroglyphs, and was quite literally in the shape of a sarcophagus. Funnily enough, our interview took place 100 years to the day of the opening of King Tut’s Tomb.

To start off, what were some of the biggest 1920s styles overall?

Sara Hume: Overall they had short skirts and tubular shapes. They also had the dropped waist and beading for evening dresses. Sometimes there was fringe, which is how we like to imagine it, not sure how widespread it was, but certainly there were some fringe-y sort of flapper dresses. There were also certain colors that were very fashionable including minty green, a sort of peachy pink color and a lot of black dresses. There was also a romantic trend. They looked back to the 18th century, and had some dresses that have panniers or hoops on the side to give this wide sort of silhouette, but with a low waist and wide hips. This was mostly seen in evening wear and wedding dresses.

The tomb opened in 1922. Did the general public read about it in newspapers and see pictures? Or did they just start seeing accessories and clothing inspired by King Tut’s tomb?

SH: I think there was a lot of fascination with Egyptians, and when looking at the dates of things Egyptian inspired, it’s possible it wasn’t just in 1922 that things started to be really popular. I think they were already really inspired by Egypt and then they were exploring it at the same time. That’s why they were really in tune with what was happening in Egypt. So you see makeup as part of that as well as the styles of the dress.

Would you say Egyptomania was mostly featured in evening wear or everyday dress?

SH: It was probably mostly evening wear with the gold, beading and the drape. They sort of mimicked a loincloth style in addition with the heavy eye makeup and sleek hair. Day dresses were not as inspired by Egypt.

Were there fashion icons or trendsetters that perpetuated Egyptomania?

SH: I think movies were a big part of setting the style [such as] Rudolph Valentino in “The Sheik” in 1921. There was a whole romance of the Middle East and Africa. Film played a big role in setting fashions.

Why do you think there was such a fascination with Egypt and the Middle East?

SH: If you think back, it was the height of the colonization of the Middle East, of North Africa. It was western control of the whole region, so politically it’s important, so there was a lot of study of the culture and learning and getting more information about that region of the world. So this created a lot of curiosity. The colonization and ornamentalism of that area has always been a romanticization of the culture. There was a focus around Egypt in the 1920s, but it’s part of a bigger fascination.

What would be some of the popular colors that specifically came from this trend?

SH: Gold was the big one. A lot of the media they would have seen would’ve been black and white pictures so it might’ve been difficult to take a lot of inspiration from the color palette. Think of a lot of white linens. They’d interpret a lot of already popular colors, so they might call a green ‘Nile green’ or papyrus.

Though brands weren’t nearly as popular then as they are now, were there any specific designers that took inspiration from the opening of the tomb?

SH: The big-name designers of the time were in France so I don’t know if any of them specifically looked to Egypt. If you look at the fashion magazines, the plates would have been associated with brands. Someone like Paul Poiret was really inspired by orientalism, such as Arabian Nights and stuff like that. Paul Poiret was the big one for ornamentalism, but the other ones went along with it. I wouldn’t think people like Chanel were as much into orientalist stuff and someone like Worth, who was an older name, would’ve followed the trends I would imagine. They would’ve all picked up on the trend, but they wouldn’t have really pushed it as their signature.

Are there other eras that have drawn from Egypt?

SH: The interest of Egypt in fashion, you see it in the 1800s, such as the cashmere shawl and turbans. When Napoleon went on his Egyptian campaign around 1800, you see it even earlier. We have this notion that they discovered something in 1920, they were certainly aware of Egypt, it’s a huge part of our culture anyway in the Bible and such. It’s always an available topic. “Cleopatra” comes out with Elizabeth Taylor, and you see fascination again. Claudette Colbert as Cleopatra too in 1934 and “Ten Commandments,” both creating a big Egypt fascination.

What would you say makes people come back to Egyptian style?

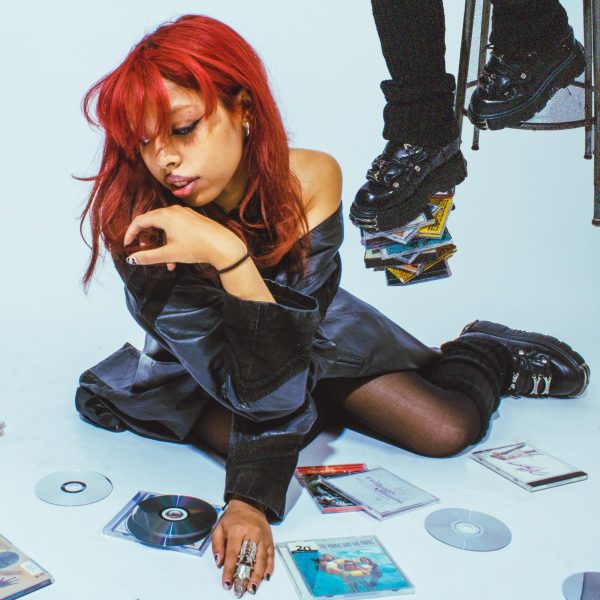

SH: There’s this fascination with Egypt in terms of mysticism and philosophical roots of Egyptian culture and the way they link to, or it resonates with people of African descent so there’s a lot of fascination in that sense and because it’s in the Bible, you know pharaohs, and the parting of the Red Sea and Moses. It’s big roots in Judeo-Christian culture. Exodus is important for Jews and Christians. You see a lot of cultural resonances to what’s going on in Egypt. I think people feel this sort of ancestry, this sort of going back to their roots and discovering who they are. Egypt is very important to early civilizations. There’s a fascination with how rich and elaborate their culture is such as the hieroglyphics and of course the pyramids. And there’s a beauty, an aesthetic appreciation of it, of the elements that you see in fashion, a lot of the time it’s a reflection of how beautiful these mummies are, the jewels, the hieroglyphics.

Would you say there could be any future cultural moments or moments of exploration that could influence fashion in the way that the 1920s was influenced by Egyptomania?

SH: Well, it’s hard to say what’s going to be discovered or found out, but I think Egypt continues to fascinate people. I think now too, there’s a moment of decolonization and efforts to be more respectful of these people’s culture. Egypt is still a country, people still live there, and we’re appropriating their culture. So I think the trend might be to have more respect for or appreciate it on your own terms, and let Egyptians speak and represent more than the way we, the west, have interpreted it. I’m actually working on an exhibition of North African fashion now, but like contemporary, but not Egypt. Egypt is sort of its own thing, sort of between North Africa and the middle east. It’s sort of culturally distinct. So it’s not as much a focus of my research, but I’ve been attentive to these tropes of colonial orientalist fascination with the region. I think the trend going forward is allowing for more self-expression for North Africans and the Middle East, a little less of the orientalist romance.

Would you consider the fashion of the 1920s appropriating Egypt?

SH: Yes. When you put it in the context of what was happening in the time, it was very colonial. I think there’s sort of a separation of what’s going on in contemporary political scenarios and then the past, that, like I said, feel they have a link to ancient Egypt. There’s a lot of different cultures that have roots. You know, like I said, it’s the Bible. People feel like these biblical stories as their heritage. There’s this sort of divorcing of Egyptians and ancient Egypt.

Did other western cultures see Egyptomania, such as Britain or France?

SH: I think the UK because they were more of the colonial power in Egypt at that point. France had long ties, I mean Napoleon was in Egypt. And France was in North Africa, Nigeria and by ‘22 they were in Morocco and Tunisia, so that whole area was a big part of the French empire at the time. And there were big colonial expositions. I think in ‘31 in Paris they had a colonial exposition. They had people from these different places, and all the colonial efforts; It was a human zoo of sorts. It was that kind of display there. Colonialism was really big at that point. Egypt was a big prize in terms of colonialism so that was Britain’s big thing, but there was a lot of French interest too. So they had parts of the middle east and parts of Africa. And you certainly see Egyptomania in France. It was all over the west.

Support Student Media

Hi, I’m Catie Pusateri, the Editor-in-Chief of A Magazine. My staff and I are committed to bringing you the most important and entertaining news from the realms of fashion, beauty and culture. We are full-time students and hard-working journalists. While we receive support from the student media fee and earned revenue such as advertising, both of those continue to decline. Your generous gift of any amount will help enhance our student experience as we grow into working professionals. Please go here to donate to A Magazine.